The seeds of packaging and Ecommerce trace their roots from ancient times to today. In our previous articles in the Putting the “E” Into Ecommerce series, we outlined:

Part 1: Ancient Commerce

Part 2: Commerce and Packaging in the Middle Ages and the Age of Exploration

Part 3: The First Two Industrial Revolutions ~1733 to 1914

The two Industrial Revolutions during this third period were:

- The Age of Mechanical Reproduction (~1733 to 1860s)

- The Technological Revolution (~1870 to 1914)

By today’s standards, the “technology” of the second industrial revolution seems less revolutionary. But at the time, it allowed the mass production of goods, which was revolutionary for its time.

1914-1945

Following on the heels of the Technological Revolution, two world wars bookended an economic expansion followed by the Great Depression. In fact, decades would pass before the Third Industrial Revolution would begin. However, this does not mean that the world of commerce remained unchanged. Far from it.

In Part 4 of our series, we explore manufacturing, packaging, and commerce from 1914 to 1945.

Commerce During World War I

The Second Industrial Revolution ended in 1914. This was the same year that Ernest Wertheimer, my father and the founder of Wertheimer Box, was born in Zilina, a small city that was part of the Austro-Hungarian empire. Today, it is a Slovak city bordering Poland and the Czech Republic. But my grandfather always said they were Hungarian.

However, two months and 14 days after his birth, Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria was assassinated. This spark ignited the Great War (World War I).

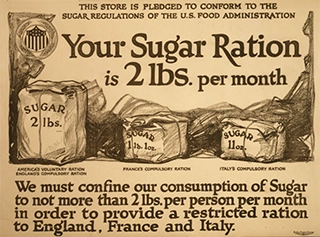

Grocer’s sign reinforces the rationing of sugar to two pounds a month.

During the war, Americans were encouraged to plant “Victory Gardens.”

Manufacturing

Europe was in chaos. Instead of using manufacturing machinery to enrich lives and enhance commerce, industrialized nations produced the commodities of war. Factories manufactured tanks, airplanes, ambulances, and weapons. Iron mining and steel manufacturing thrived.

Inflation was rampant and impacted food prices. Under Woodrow Wilson’s Administration and headed by Herbert Hoover, the U.S . Food Administration encouraged people to decrease wheat, sugar, and meat consumption. At the same time, the Food Control Committee distributed ration cards to enable adequate amounts of food to go to the U.S. military and starving Europeans.

Liberty loans, also known, as war bonds, were a quick way to generate large amounts of cash to buy munitions.

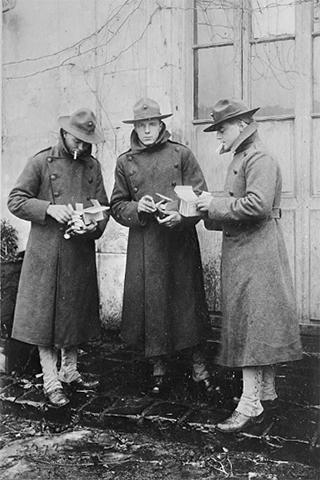

WWI soldiers opening American Red Cross care packages in 1917.

Packaging During World WarI

Most shipping cartons began shifting from wooden crates to corrugated containers about 1900—however, munitions shipped in traditional wooden crates and boxes during WWI.

By contrast, the military shipped ration boxes in heavy corrugated boxes covered in kraft paper wrapped with string. Contents contained tinned meats, pork and beans, and jam; items in chipboard boxes such as cigarettes, soap, and matches; and cookies and chocolate wrapped in paper.

Moreover, families and loved ones sent care packages to their soldiers overseas. They mailed knitted sweaters and socks. Within the corrugated cartons, they also sent nonperishable food in paperboard boxes wrapped in string. Many of these food items were in tin cans or containers.

Government officials defined the packaging structure and weight limits to control the parcel volume driven by care packages (under 7 lbs.). By 1918, the government also required that soldiers submit an official request to enable them to receive a care package.

At the same time, The American Red Cross created “Christmas coupons” for soldiers to receive three-pound care packages.

The Great War Ends

After the loss of millions of lives, World War I ended on November 11, 1918. By the war’s end, food prices had risen astronomically.

Consumerism and Manufacturing in the 1920s

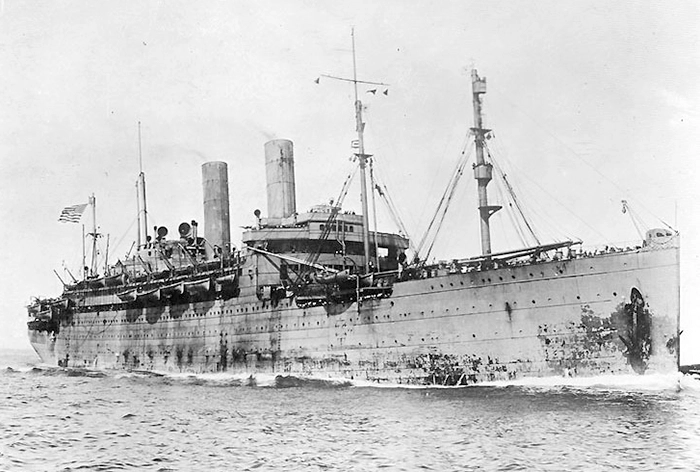

The Wertheimer family steamed to the United States on the passenger ship, The George Washington. Renamed, the SS George Washington, she was also a warship during WWI.

The Wertheimer Family Emigrates to the United States

Six years after the “War to end all wars” concluded, eight-year-old (or ten-year-old, there is some discrepancy about his age) Ernest Wertheimer (my father) boarded The George Washington with his older sister Regina, age ten (my Aunt Jean), and younger brother Geza, age 4 1/2 (my Uncle George). My grandfather, Nathan, had arrived in Portland, Maine, in November 1923. So, the children traveled with my grandfather’s second wife. (My grandmother, Ilona, had died in 1921.)

The steamship sailed from Bremen, Germany, and arrived in New York City on October 26, 1924.

My grandfather, dad, aunt, and uncle then traveled to Chicago by train. As was the day’s practice, they likely would have been segregated from native-born American passengers into separate train cars for “foreigners.” Chicago’s Union Station did not open to the public until 1925, but the LaSalle Street Station is a likely possibility of their Chicago entry.

The Roaring Twenties

During this same time, manufacturing, retail, and all types of commerce skyrocketed. Excess and consumption was the order of the day. Consumerism, an impulsive desire to spend money, drove Americans to buy more.

Woman tuning a radio in 1920. Radio promotions helped to fuel Americans’ consumerism.

Boy listens to the radio while getting his hair cut in a barber shop, 1921. Advertising agencies would garner specific radio sponsorships for brands. They would also write the brand’s use into the radio scripts.

U.S. Manufacturing in the 1920s

Several factors led to manufacturing growth:

- Electric motors

More efficient electric motors replaced steam power. - Cost of Electricity

The cost of electricity declined from 1914 to 1917, and factories used the resource to light and power their plants. - Assembly lines

Assembly lines standardized and boosted the mass production of autos, electronics, ready-made apparel, and beauty products. - Credit and installment plans

Prices dropped, and “luxury” items became available to more public—especially with the swelling use of credit and installment plans. In addition, air and ground travel expanded. - Rise of home appliances

Home appliances became commonplace. Radios, sewing machines, vacuums, phonographs, and washing machines graced many homes. Refrigerators replaced ice boxes. - Radio promotions

Furthermore, radio ads and sponsorships helped sell products.

Man stitching corrugated at a corrugated cardboard plant in 1924. Note the wooden bins stacked on the right.

Factory workers manually assemble typewriters.

Assembly line in ball bearing factory, 1923.

Packaging in the 1920s

Corrugated boxes continued to replace wooden crates and bins. Goods were shipped across the country to satisfy Americans’ passion for buying household appliances and other comforts.

The 1920s Bubble Continues to Bloat

However, the prosperity of the Roaring Twenties was a tenuous bubble about to burst.

Commerce During the Great Depression

The Roots of the Great Depression

When the stock market crashed on “Black Thursday” in October 1929, the Great Depression ensued. Besides the crash, other factors led to this global economic downfall, including:

- Overspending during the Roaring Twenties.

- Poor regulatory oversight of the stock market.

- The collapse of U.S. banks (1933).

- Years of agricultural losses.

- The inexperience of the Federal Reserve.

- Overproduction resulted in deep discounts and minimal (if any) profits.

A cycle of low product demand, leading to company layoffs, then decreased spending of those without income, leading to low product demand, followed by more staff reductions, and so forth.

Herbert Hoover’s reluctance toward public relief of the homeless and hungry, which he believed would “weaken people’s character.”

U.S.-centric isolationism along with the Tariff Act of 1930 and other tariffs that reduced world trade. Imports and exports tumbled by 30%.

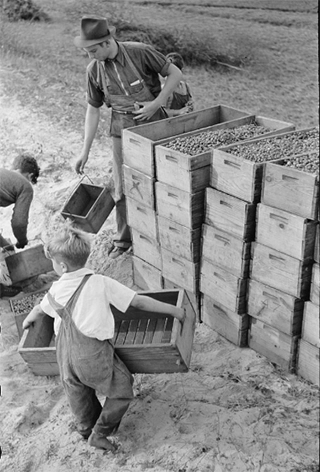

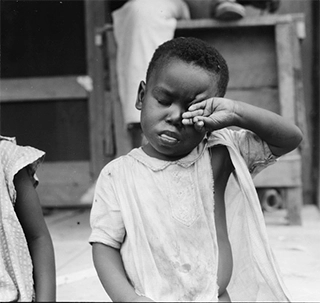

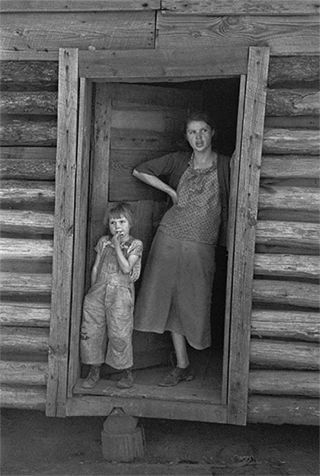

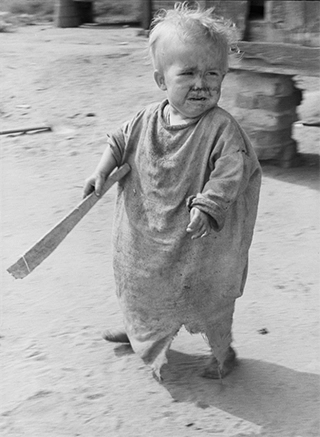

Children of the Great Depression

Children of the Depression endured some of the harshest consequences. Missed meals led to malnutrition. Infant mortality and child labor climbed. Children worked grueling hours in factories. Many were sent away to relatives, strangers, orphanages, or labor farms. Others were left orphaned and forced to fend for themselves. Children were often traumatized and forced to become “adults” too soon.

Mother and daughter, squatters in Missouri, 1938.

Nine-year-old child picking beans, 1939.

Young boy lifting wooden crate for packaging cranberries in New Jersey, 1938.

Boy harvesting onions from a Minnesota onion field, 1939.

Child of the Great Depression in Mississippi, 1936.

Wife and child of sharecroppers in Alabama, 1937.

Coal miners child, West Virginia, 1939.

Young boy harvesting cranberries in a New Jersey cranberry bog, 1938.

North Carolina sharecropper’s child, 1935.

Retail During the Great Depression

Consequent to poverty, consumer spending was minimal during this period. It dropped from $77.5 billion in 1929 to $45.9 billion in 1933. Retail spending dropped by nearly one-half (49%), and food sales dropped by 37%.

Instead of buying groceries, people planted gardens, canned food, skipped health and dental care, and bought old bread. They waited in long bread lines. They went hungry. About 5% of food stores closed. Supermarket stores emerged with deeply discounted prices. And the “chain store act” of 1936 attempted to thwart discount abuses.

At the same time, the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act began to require that beverages, foods, drugs, and cosmetics be proven safe.

Despite these hardships, a few food innovations launched during the Great Depression:

- Birdseye brand frozen foods

- Snickers candy bars

- Gerber baby cereal

- Kraft Macaroni and Cheese

- Hormel’s SPAM

Retail Packaging During the Great Depression

Tin Cans

Machine-stamped tin cans continued to house food, such as oysters, meats, beer, vegetables, condensed milk, and fruit. Even Colgate tooth powder came in a can.

Boxes and Cartons

Corrugated folding boxes, which could be shipped flat, remained a staple for manufacturers. However, unlike today’s glued containers, they were held together by tape. Additionally, paraffin-coated folding cartons housed ice cream and butter.

New Packaging Associations

Packaging companies joined forces to survive the economic downturn—two associations formed during this period. The Paraffin Carton Association was formed in 1929, and the Folding Paper Box Association of America (FPBAA) was established in 1993. (The latter is now the Paperboard Packaging Council.)

Reuse of Packaging

Packaging was almost always reused. Cookie tins became lunch boxes. Corrugated boxes stored household items.

Likewise, women repurposed the cotton cloth of flour or seed sacks to sew garments for their families. Flour companies responded (and competed with one another) by printing attractive patterns on their flour sacks.

During the Great Depression, women began making clothes from the cotton of flour bags and feed bags. This dress was sewn from the fabric of a feedbag.

Packaging as Marketing Vehicles

With its colorful printed exterior, food packaging became a “silent salesman.”

Furthermore, creative food companies began packaging additional promotional items to be discovered after purchase. For example, “Depression Glass,” machine-made and patterned teacups, saucers, bowls, and other types of dishware, were included inside Wheaties boxes and Quaker Oats containers.

Despite the efforts of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal, the Great Depression gripped the United States until 1941.

World War II

In September 1939, Hitler invaded Poland. Both England and France declared war on Poland’s aggressor: Germany. Thus, WWII broke out.

Wertheimer Box Launches

One month later, Ernest Wertheimer (my father) left the insurance business. Just as Dustin Hoffman’s character, Benjamin, was encouraged by his dad’s friend to go into “plastics.” A friend of my dad’s told him to leave insurance and “get into corrugated.”

Consequently, the Wertheimer Box and Paper Corporation launched in October 1939. At first, the company was an entrepreneurial brokerage for corrugated manufacturers in the Chicago area.

The United States Enters World War II

At the same time, as the Chicago company was taking off, World War II continued to escalate. By 1941, it was being fought in the Pacific, Europe, and North Africa.

The United States, however, had a U.S.-centric, nationalistic viewpoint. The seeds of isolationism went back as far as George Washington.

That spirit changed on December 7, 1941, when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, an American territory.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt joined the Allied powers against the Axis alliance (Germany, Italy, and Japan). This unprovoked attack sparked outrage among Americans.

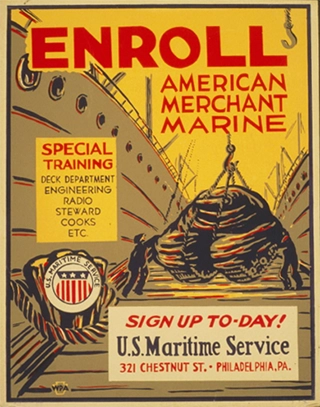

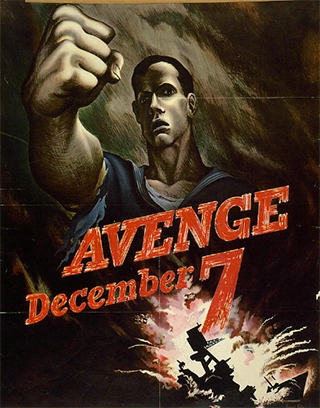

U.S. recruitment poster encourages men to enroll in the American Merchant Marine, 1941.

U.S. recruitment poster reflects the outrage Americans felt after the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

Wertheimer Box During World War II

My father was no exception. Like most Americans, he stepped up to serve his country. He put his brokerage business on hold and enlisted in the U.S. Navy. He served as a trainer at the Great Lakes Naval Training Station in the city of North Chicago, IL, from 1941 to 1945. The base trained a million men during WWII.

This cash register factory in Dayton, Ohio, was retooled to manufacture gun magazines. Photograph was taken in 1942.

Manufacturing Shifts to World War II Commodities

Once again, U.S. manufacturers focused on the war effort: aircraft, artillery, tanks, and trucks. As a result, the United States supplied nearly two-thirds of the Allied military equipment.

Already the world’s largest manufacturing supplier, the United States doubled its production. A whopping six million of these factory workers were women—usually with wages less than half of their male counterparts doing the same work.

Retail Rationing Returns to the Home Front During WWII

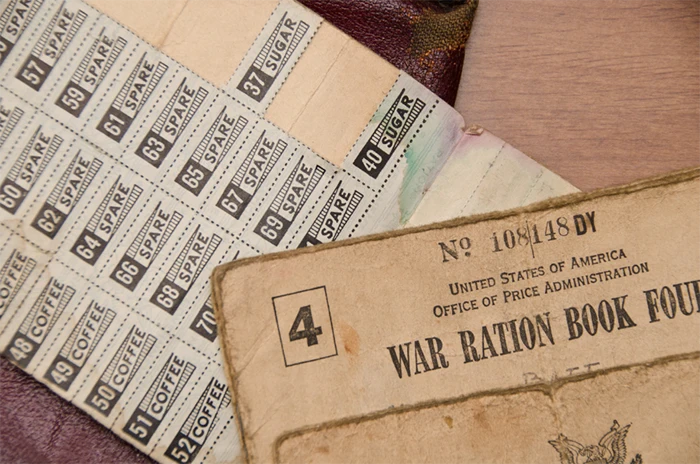

By January 1942, Americans on the home front experienced rationing points that came as a book of stamps. Sugar, tires, gasoline, meat, coffee, butter, canned goods, shoes, and many more were among the rationed goods.

Food, gas, shoes, metal, paper, and rubber were in short supply. Farm tractors, delivery trucks, first responders, and physicians had to apply to rationing boards to fill their tanks with gas above their assigned rations levels.

Perhaps ironically, cigarettes, whiskey, and fresh produce were unharmed by rationing. Still, shortages of these coveted supplies occasionally occurred.

Three consequences followed:

- The rise of Black-Market goods.

- Expansion of organized crime and gangs that counterfeited rationing coupons, especially gasoline stamps. They also stole rubber tires and other sought-after goods, then sold them above market prices.

- Propaganda campaigns rose to an art form both here and abroad.

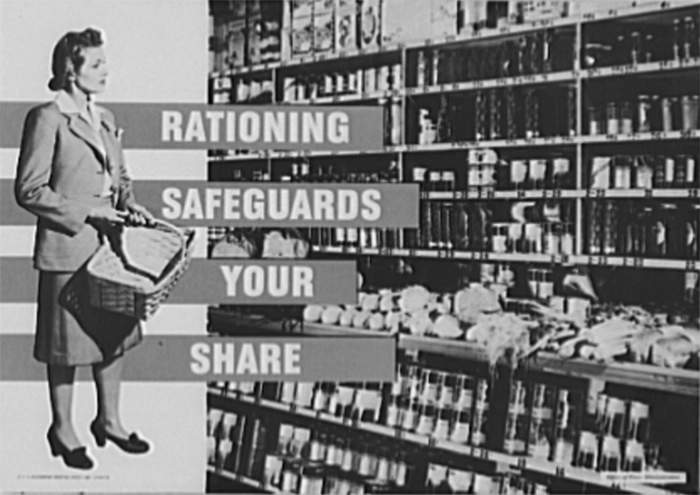

WWII propaganda poster reinforces the idea of rationing. It reads, “Rationing safeguards your share.”

As a result, Americans planted “Victory” gardens and canned their foods, freeing up manufactured goods for the boys at war.

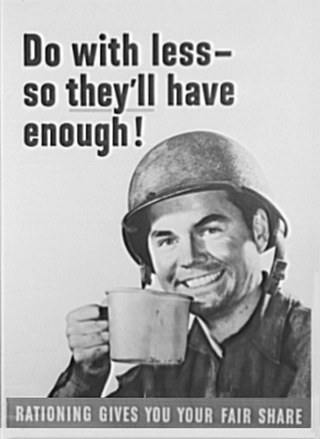

WWII poster reads, “Do with less so they have enough, everybody gets their fair share.”

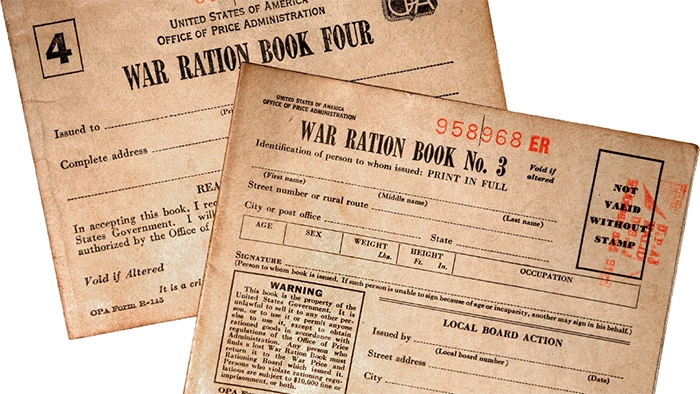

World War II ration books No. 3 and No. 4. Book 3 included eight pages of stamps, four for meat and four for clothing. The clothing rationing program was never put into effect.

Woman reads U.S. government information about rationing.

Ration stamps from Book 4 were for food commodities and were valid in late 1943. The remaining stamps in the book read coffee, sugar, and spare.

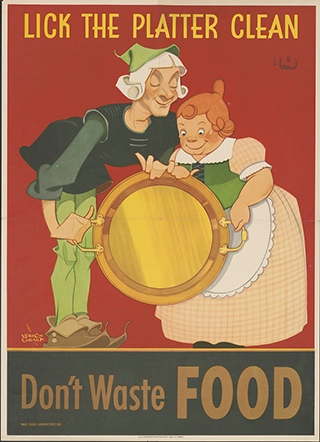

WWII poster encourages Americans not to waste food. It shows Jack Sprat and his wife and reads, “Lick the platter clean.”

Women at Work During WWII

In addition, Rosie the Riveter recruited women for defense industries. By 1945, one in four married women worked outside the home.

Women worked in all sectors.

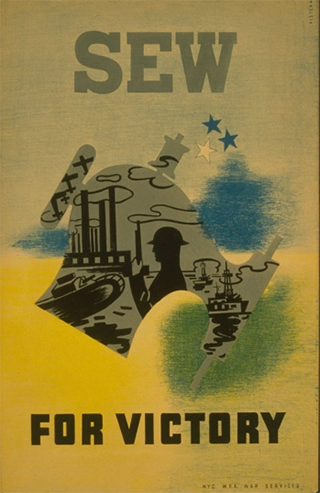

U.S. WWII poster from 1947. Fabric was needed for the war effort.

Retail Fashions During WWII

Food, gasoline, and tires weren’t the only rationed retail items.

The war also gobbled up natural fibers and cloth: cotton, silk, nylon, wool, leather, and rubber.

Women’s Garments Regulated During WWII

In 1942, the War Production Board Regulation passed L-85. L-85 dictated clothing fashions only for women. The new regulation:

- Restricted color choices.

- Reduced skirt lengths.

- Forbade hems and belts wider than two inches.

- Prohibited cuffs.

- Narrowed pants and jackets.

- Cut pockets to one per garment.

- Prevented unnecessary adornments like ruffles, puffed sleeves, hoods, pleats, and more.

Elastics were removed from undergarments.

Likewise, nylon stocking production halted. Instead, women applied makeup down the backs of their legs to create the illusions of nylon seams. Meanwhile, the nylon factories swung to parachutes, ropes, mosquito netting, flak jackets, and more.

Only bridal gowns and maternity clothes remained unscathed by L-85.

Propaganda posters cried, “Use it up – Wear it Out – Make it Do!” These posters also encouraged women to wear synthetics like rayon stockings and undergarments.

Furthermore, utility was essential. For example, women’s “siren suits” became popular in England. These slip-on jumpsuits were perfect for nighttime air raids. Overseas, women’s bags also sported locations for gas masks.

U.S. WWII poster from 1947. Fabric was needed for the war effort.

Men’s Apparel “Shrinks”

Although men’s clothing was not regulated, it also underwent some drastic changes.

Wartime civilian fashions for men consumed less fabric. Double-breasted suit jackets, the vests of three-piece suits, wide lapels, and long shirts shrunk. Manufacturers replaced them with single-breasted, two-piece suits, narrow lapels, and shorter shirt lengths. Cuffs and pocket flaps vanished. Mismatched jackets and trousers became acceptable. Furthermore, the typical second pair of trousers, once bought with a suit, evaporated to a single pair.

Packaging During WWII

As in WWI, field rations were shipped overseas in thick corrugated cartons and wooden crates. Some contained tin cans of food. Others contained additional corrugated or chipboard boxes with food and other supplies. In addition, for those in the jungle, field rations included waterproof cloth bags to store food.

As they did during WWI, families and loved ones sent care packages to men and women overseas.

Additionally, the American Red Cross used corrugated cartons to ship parcels to prisoners of war (POWs). These included food, medical supplies, clothes, toiletries, and seeds for gardening.

A historic photo of its POW First Aid Safety Kit displays a corrugated box containing a chipboard box filled with supplies. The packaging also includes a corrugated tube around the chipboard.

Army K-ration kit in cardboard boxes. Typically, boxes were taped instead of being glued. (Also shown in the featured image.)

Effects on Retail Prices

According to U.S. propaganda posters, the cost of living increased by nearly 26% by 1944—but not as astronomically as during World War I, when living costs soared 65% during (supposedly) the same period.

This is because the government applied lessons learned during The Great War:

- Instead of encouraging rations at home, it required them.

- It also enforced regulations.

- It bestowed broad powers to the Office of Price Administration. Many, mainly organized retailers and manufacturers, attempted to thwart those powers.

Moreover, widespread U.S. propaganda generated support for the war and the sacrifices made.

WWII Concludes

On September 2, 1945, the war ended with the unconditional surrender of the Axis alliance.

Six years and one day after it began, 60-80 million people had perished from the Earth. Among those who lost their lives were 6 million Jews killed in Nazi concentration camps.

In part 5, we’ll discover the march toward Ecommerce in the Post WWII era.

References

- Atlas Obscura, Gastro Obscura. The depression-era glassware came in boxes of oatmeal.

- BB Print Source. Find a print and packaging trend to boost your brand.

- Can Manufacturers Institute. History of the can: an interactive timeline.

- Encyclopedia of Chicago. Great Lakes Naval Training Station.

- The Food Historian. World War Wednesday: cost of living in two wars.

- Gail Academic OneFile. American railways and the cultural landscape of immigration.

- Historic Mysteries. More than packaging? The dark secret behind pretty bags of flour.

- History. WWII: Rosie the riveter.

- Insider, Personal Finance. 7 causes of the Great Depression, and how the road to recovery transformed the US economy.

- The Jolly Man Letters. A wonderful Christmas surprise – my WW1 ration parcel.

- Khan Academy. 1920s consumption.

- Library of Congress, Research Guides. Consumer Advertising During the Great Depression: A Resource Guide.

- National Archives, Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum. Great Depression facts.

- The National WWII Museum, New Orleans. Rationing.

- The National WWII Museum, New Orleans. Research starters: women in World War II.

- The Ohio State University. A history of packaging.

- Oregon Secretary of State, Life on the Home Front: Oregon Responds to WWII. Rationing: a necessary but hated sacrifice.

- Paperboard Packaging Council. Our roots: PPC history.

- PBS, The War. War production.

- PhD Essay. Packaging is a silent salesman.

- Progressive Grocer. New Deals of the 1930s.

- Questmaster.us. WWII crates, boxes and containers, page 1 rations.

- Sarah Sundin, Today in World War II History. Make it do: clothing in World War II history.

- Smithsonian, National Museum of American History, Behring Center. Dressing for war.

- Study.com. Mass production in the 1920s.

- Study.com. What was consumerism in the 1920s?

- UnitedStatesNow. What Were the Effects on the Children of the Great Depression?

- WWII US Medical Research Centre. WWII American prisoner of war relief packages.

Doug Wertheimer

Get More Industry News Like This

Welcome to the Wertheimer Family! We'd like to keep you up to date with industry changes and news. Subscribe to receive our occasional news, updates and articles direct to your in-box.